The music-loving brain

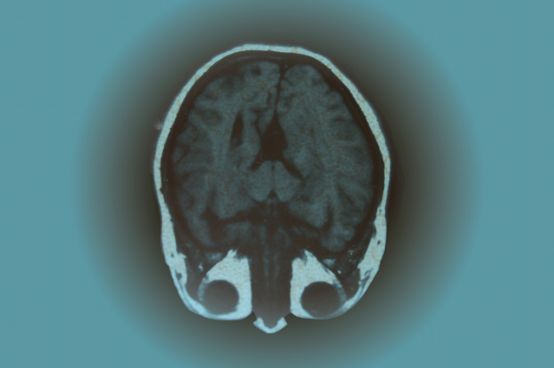

Neuropsychologists are accumulating evidence of the power and importance of music. The erroneous idea that this art form could disappear without changing human life is no longer tenable.

Conceived in three parts, this fascinating book, written by researchers working mainly in French universities, first looks at the universality of music-induced emotions. The central section presents the most recent scientific discoveries, in particular the interactions between language and music, the beneficial influence of the latter on cognitive abilities and brain plasticity. The art of combining sounds is no longer seen solely as a psycho-affective regulator, but also for its neurostimulatory and neuroprotective qualities. This opens up a vast field of research into the therapeutic potential of music.

The final section looks at some specific cases: amusia, virtual reality, auditory abilities of the blind, positive and negative emotions, and finally contemporary music. The latter is a good example of implicit learning:

"The ear and the musical brain gradually adapt to the structures of contemporary music, even to the complex structures of the serial system, but without being aware of it. So, even if the listener is very disoriented by this music, his brain integrates its organizations and, as a result, modifies his listening habits" (Emmanuel Bigand and Philippe Lalitte, chapter Contemporary music: a challenge for the brain, p.191).

For other types of music, too, there's no need for explicit prior knowledge: the brain becomes sensitive to the musical structures to which it is exposed, even passively. Their understanding depends on the listener's acculturation, which generates perceptual expectations; when these are not met, the brain reacts to these surprises in the same way as it does to changes in the syntactic structure of spoken language. In addition to the phenomenon of acculturation, emotional universals exist, recognizable by everyone, which explains why the profound effect of music extends far beyond the restricted spheres of cultivated music lovers, since anyone can potentially be touched by a work by Beethoven or Puccini (except in clinical cases such as amusia), and why, irrespective of personal artistic taste, some music acts against stress and the production of cortisol, while others exert the opposite effect.

Musical practice

As for the active practice of music, there is growing evidence of its beneficial effects. Here are just three examples: it enhances perception of the emotional content of words, as well as of their meaning (hence the fact that musical children have a better understanding of language, a richer vocabulary, and greater facility in learning foreign languages); the coordination of a musician's two hands requires a rapid connection of information between the two motor cortexes, resulting in greater communication between the two hemispheres; gray matter decreases less with age in musicians than in non-musicians. Functional and structural changes in the brain appear after just one year of musical practice.

Reading this book, you can also learn, among other things:

- what is the impact of music on the brain and intellectual capacities, or its action against the effects of cerebral aging?

- why musicians are less likely to develop neurodegenerative diseases

- why rats' spatial abilities are stimulated more by Mozart than by Glass

- which areas of the brain identify the feelings conveyed by music

- what role does music play in memory development?

- what is the beneficial effect of musical practice on foreign language learning?

- what is the difference between semantic and episodic memory?

- what role does music play in the cognitive and emotional rehabilitation of people with brain damage?

- how the reorganization of brain areas enables blind people to hear better and faster

- what is the origin of focal dystonia?

- how to reduce the aggressive nature of tinnitus

In short, as Daniele Schön writes in chapter Musical practice and brain plasticityAll these results should encourage the world of education to give a much more important role to music teaching. Music should cease to be a neglected discipline in the school curriculum. Without disrupting pupils' timetables, and at little cost, we could encourage this social and recreational activity which, at the same time as creating millions of new connections in the brain, strengthens links (and quality links) between people." (p.98)

Le cerveau mélomane, book editor Emmanuel Bigand, 111 p., € 21.00, Belin, Paris 2014, ISBN 978-2-8424-5118-9