Traditional music

Three new books examine the music of North American Indians, the shakuhachi flute and Japanese musical aesthetics, and the music and instruments of the Kurdish culture of Iran and Iraq.

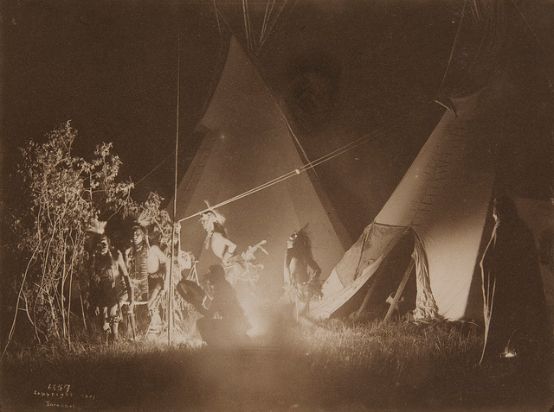

First published in 1926, American Indians and their music by ethnomusicologist Frances Densmore, just published in translation, is one of the first major contributions in this field, the fruit of decades of research by its author among the many tribes she has worked with over the years, highlighting their similarities and differences, describing their customs and defining their social context. After a general presentation of some of the cultural aspects of the 342 Indian tribes of North America, from the Pueblos of New Mexico to the Eskimo peoples of the far north, this highly informative booklet turns to the study of the various song forms, which are striking for their frequent changes in bar length, with irregular alternation, and for the fact that tempo can differ between the singer and his drum accompaniment. Individual or collective invocations of spirits or supernatural help, some songs accompanied ceremonies, while others were believed to possess magical powers, healing for example. Still others were used for games, dancing, seduction, warrior homage; melodies could also be received during a dream. The author explains the poetics and themes of the texts, which also include vocalized songs with few or no words, secret languages intended for initiates, languages invented during dreams, ancient lyrics that the performers no longer understand at all, or melodies in the language of another ethnic group. Tribes had their own repertoires, but they could also exchange songs. A large part of the book is devoted to instruments: recorders and whistles, percussion (mainly various tambourines, drums and idiophones); only the Apaches used a stringed instrument, the violin.

The subtitle of Bruno Deschênes's book on the shakuhachi bamboo flute, "A Tradition Reinvented", clearly indicates the extent to which forced Westernization, from the end of the shogunate onwards, has profoundly altered the use of this instrument, long associated with a guild of monks, allowing it to spread more widely and making it popular as far afield as Europe and North America. In return, Western music has for some decades now been influencing playing styles, tuning, intonation and even melodies. In addition to its history, playing techniques and notations, the author discusses the evolution of shakuhachi construction and its various models (in addition to the standard length that gave the instrument its name, there are smaller and longer shakuhachi, up to double the length). He also analyzes the melodic structure, or rather the arrangement of motifs representing, metaphorically speaking, states of mind. Through practice and self-discipline in artistic apprenticeship, or more precisely in the way of art (geidō), it is a maturing of the personality and a transformation of the self that are aimed at, more than mere technical skill. The book is also an introduction to traditional Japanese thinking, which is based on experience and feeling, and in which aesthetics are pre-eminent, underpinning every activity, every gesture. Also discussed are "ma", a polysemantic concept encompassing space-time, and the importance of the correct form of acts and rituals, as relational elements, but also as structuring elements of society as much as of the work of art. The final, and most developed, chapter deals with Japanese musical aesthetics, exploring in greater depth certain notions already encountered (metaphors, intersubjectivity, the role of transmission from master to disciple).

Situated at the confluence of Arabic, Persian and Turkish influences, yet possessing its own individuality, Kurdish music remains little known. Mohammad Ali Merati's study focuses primarily on early non-religious songs (lyrical, elegiac, epic), some of which are based on traditions (Yazdanism and Zoroastrianism) whose origins date back to the pre-Islamic period. Some of these songs can also be used in a religious context. The central part of the book is devoted to modal forms - here classified for the first time - and their structure, with full analyses of examples transcribed in score. Maqam refers to both a musical system and its specific applications: each maqam has its own scale organization, color and melodic progression (often over two octaves); in the Kurdish sense, however, the term refers more to a standard melody serving as a model for the elaboration of songs. The final chapter describes the musical instruments and techniques used by the Kurds, including the zurnâ oboe, the shemshâl flute, the tanbur cistre and the dahaf drum. In the various countries of Central Asia and the Middle East, we find more or less the same instruments, sometimes with quite different names (the famous Armenian duduk is called bâlâbân in Turkey and narme-nây by the Kurds).

Frances Densmore: Les Indiens d'Amérique et leur musique, 128 p., € 10.00, Editions Allia, Paris 2017, ISBN: 979-10-304-0515-6

Bruno Deschênes: Le Shakuhachi japonais. Une tradition réinventée, 256 p., ca. € 26.00, Editions Harmattan, Paris 2017, ISBN 978-2-343-11170-4

Mohammad Ali Merati: Les Maqâms anciens et les instruments de la musique kurde d'Iran et d'Irak, 236 p., ca. € 24.00, Editions Harmattan, Paris 2016, ISBN 978-2-343-09470-0