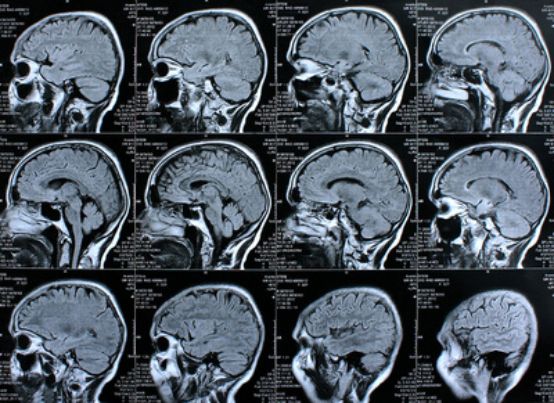

Music can shape the brain

Les éditions du Seuil have reissued a paperback version of a fascinating book linking music and neurology. They have also published a book on the state of digital music.

Little-known and surprising worlds

With his great talent for popularization, Oliver Sacks shares his experiences and knowledge as a neurologist particularly interested in music and its effects. Although a few naïve remarks here and there show that the author has no professional musical or musicological training, the many anecdotes give us access to little-known and surprising worlds, and also help us to grasp the fundamental importance of music for human beings.

There are many cases in this fascinating book, including a composer who regains perfect hearing after composing a complex work, an autistic man who knows 2000 operas by heart, a total amnesiac who can nevertheless continue to interpret his repertoire perfectly on the piano or organ and conduct choirs, an old lady who vegetated by listening only to variety shows and suddenly becomes more active again after listening to classical music, aphasics who recover part of their language thanks to music therapy, where conventional speech therapy had failed. Even more astonishing: people who have been struck by lightning and suddenly become sensitive to music, or even musicians, or Parkinson's and postencephalitis sufferers who can regain normal movement by listening to music, or even be able to play the piano.

Sacks also describes the different types of amusia: the absence of a sense of pitch, dystimbria (which makes the most beautiful music sound like pots and pans), the inability to understand or recognize a melody, the impossibility of understanding harmonies as anything other than superimposed sounds, and the rarer dysrhythmia. Among other things, he tells us that synesthesia seems to be more common than assumed, especially in childhood, and often disappears by adolescence; he describes the origin of auditory hallucinations, when people believe they are actually hearing music outside themselves, when in fact it's just a creation of their mind. Finally, reaction to music remains preserved even at an advanced stage of dementia, and musical memory can persist long after all other forms of memory have disappeared. Patients who are unable to react to music continue to respond emotionally, and even recover certain memories in this way.

Oliver Sacks, Musicophilia - Music, the brain and us, translated from English by Christian Cler, 480 pages, € 25.00, Editions du Seuil, Paris 2012; Livre de poche : 512 pages, € 10.00

Dematerialized music

Joseph Ghosn's book, half an inventory of the practical and sociological aspects of the digitization of music, observed in the field of variety music, half a journalistic overview (with simple reproductions of interview excerpts), presents a portrait of an era where notoriety is built up even before the release of the first record, and where an artist needs thousands of streaming listens before he or she can earn a single franc. A world where, on a site like SoundCloud, an average of ten hours of sound are published every minute, an exponential accumulation of music available to everyone (as on Youtube) and available outside the concert context, in a multiplication of possibilities. In the transition from vinyl to CD, and then to mp3 files, music has become progressively "dematerialized". It becomes available even without being edited. This "uninhibited" approach to music has led to the emergence of new ways of distributing it, such as Biophilia by Björk, conceived directly as a sum of applications for iPad, or a few situations that border on the absurd, for example when the singers' daily lives told to their fans on Facebook sometimes count for more than their musical output.

Joseph GhosnMusiques numériques - Essai sur la vie nomade de la musique, 224 pages, € 19.50, Editions du Seuil, Paris 2013