Jaques-Dalcroze and rhythmics

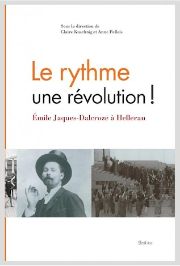

To mark the 150th anniversary of the birth of Emile Jaques-Dalcroze, composer and inventor of the famous eponymous rhythm, a brochure and book were published in 2015.

In a pleasant, richly illustrated booklet, Jacques Tchamkerten presents a biography of the composer, who began his career both as an author of serious works and as a successful chansonnier. In 1903, he began writing rhythmic gymnastics, which immediately met with great acclaim - a success that overshadowed his other compositions, including an abundant output of piano pieces, operas and orchestral works. He then devoted himself entirely to developing his method; his compositions, with their greater formal freedom, increasingly reflected his pedagogical concerns. Rhythm schools sprang up all over the world.

As for the book, while it describes the origins and specific features of Jaques-Dalcroze rhythmics, it is mainly devoted to a major place of artistic experimentation in pre-war Europe, It had a fundamental influence on modern dance (including the original choreography of Le Sacre) and the performing arts, and its demonstrations attracted the likes of Claudel, Diaghilev and Nijinsky, Hofmannsthal, Le Corbusier, Rachmaninov and Max Reinhardt. For three years, the garden city of Hellerau (near Dresden) and its Rhythmic Institute were at the center of a visionary and pioneering adventure, brought to an abrupt end by the First World War. However, the dispersal of the institute's members spread innovations in choreography, acting, staging, lighting and, of course, rhythmics, and disseminated a pedagogy based on the blossoming of pupils and the development of their spontaneity. The aim was also to re-harmonize, individually and collectively, through rhythm, human beings suffering from the alienation of industrial work and disconnection from nature. Thus, rhythmic gymnastics, initiated for music, evolved into education through music. Challenging the then-common belief that a sense of rhythm is innate, Jaques-Dalcroze taught flexibility, breathing, and the liberation of the body and gestures. He wanted to turn the whole body into an ear, promoting a living art form and joyful learning. Around this exceptional pedagogue, as gifted for music as he was for the performing arts, we find personalities such as Adolphe Appia and Alexandre Salzmann (the book contains several biographical notes). The book concludes with some thirty current testimonials and a chronology ranging from Jaques-Dalcroze's birth to the present day.

Jaques-Dalcroze's legacy is immense, multi-faceted, and we have not yet exhausted the possibilities of its development, whose ramifications continue to unfold in fields covering not only music and movement, but also space, scenography and stage lighting; whose initial pedagogical intuition covers the study of the brain and nerve connections, and whose applications range from pedagogy to medical science, all through the wonderful and ineffable tool that is music.

(Irène Corboz-Hausammann, page 17 of Le rythme, une révolution)The aim of all these exercises will be to increase psychic concentration, clearly organize the physical economy, enhance the personality and, thanks to a progressive education of the nervous system, develop sensitivity in insensitive or not very sensitive subjects and, on the contrary, regulate nervous reactions in hypersensitive or disordered subjects.

(quote from Jaques-Dalcroze, op. cit., page 50)Isn't it a pleasure of the highest order to be able to translate freely and in one's own way the feelings that move us and that are the very essence of our individuality...?

(quote from Jaques-Dalcroze, op. cit., page 58)

Jacques Tchamkerten, Émile Jaques-Dalcroze compositeur, Belles pages de la Bibliothèque de Genève, 54 p., Fr. 15.00, La Baconnière Arts, 2015, ISBN 9782940462162

Rhythm, a revolution! Émile Jaques-Dalcroze à Hellerau, edited by Claire Kuschnig and Anne Pellois with the collaboration of Martine Jaques-Dalcroze, 296 p., Fr. 39.00, Éditions Slatkine, Genève 2015, ISBN 9782832107065