Writings by Ravel and other composers

Presentation of four recent collections of writings by great musicians: the French Ravel and Grisey, and the Germans Zender and Stockhausen.

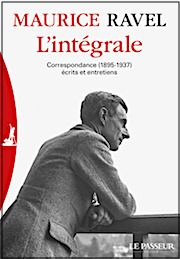

The publication by Editions Le Passeur of the most complete possible edition of Ravel's writings, interviews and surviving correspondence is rightly regarded as an editorial event, all the more eagerly awaited since to date only anthologies and documents scattered across several magazines have appeared. In addition to some 1,800 letters, cards, telegrams and other pneumatics, painstakingly researched, patiently collated and meticulously annotated by the man responsible for this edition, Manuel Cornejo, he has added over 700 documents, letters sent to Ravel and correspondence from third parties about the author of the Water games. He has, however, left out duplicates and administrative correspondence that would have been of more interest to researchers and biographers than to readers - so the title "complete" is not the most appropriate term. It also includes 148 essays, interviews, open letters, petitions and music criticism articles, as well as, in the appendix, a wealth of documents relating to the composer. In view of his notoriety, we remain perplexed by the sheer number of letters that have disappeared, whether destroyed, unlocated or in private hands that keep them inaccessible - readers are encouraged to pass on any unknown documents to the Association des Amis de Maurice Ravel. In his concise correspondence, we find a Ravel full of life and verve, who does not indulge in lengthy theoretical or aesthetic dissertations, but is willingly playful, complaining about his laziness (very relative for this hard worker), sharing his hesitations about his involvement in the First World War, enthusing or confiding his sorrows or worries.

Gérard Grisey

Too soon lost, Gérard Grisey is best known as one of the founders of the so-called spectral school, although paradoxically he himself had an ambivalent relationship with this term, as this compositional technique formed only one aspect of his music. His passion was not only for the discovery of new sound spaces, but also for the structuring of time, which was often dilated. In this new, expanded edition, published by MF, we find, on the one hand, all the significant writings of the author of the Acoustic spaces - seven texts of varying length devoted to his principles of composition, presentations of his own works and various other short articles or notes on a variety of musical subjects (the language and function of music, its place in society and teaching, new technologies, concise accounts of a few fellow composers, etc.) - as well as a number of interviews, extracts from letters and diaries.

In his enlightening preface to this collection, Guy Lelong evokes three major factors underlying Grisey's conception of music: the unification of the sound field, where the basic unit is no longer the note but the frequency, thus integrating all sound phenomena, in interaction with the knowledge of modern acoustics; a process of oriented transformation, progressive metamorphoses with threshold and tipping effects, similar to a path where predictability and unpredictability alternate; perception in real time, based on the psychology of perception and attention to the comprehensibility of the work. In short, it's a musical way of thinking that takes into account the physical, biological and psychological aspects of interactions between sounds and listeners.

Hans Zender

Renowned both as a composer and a conductor, Hans Zender is also appreciated across the Rhine for the breadth of his reflections on music and art. Highlighting the failure of post-Hegelian historical utopias and the end of the normative illusions of the 1950s avant-garde, he calls for the development of a tolerance that welcomes different aesthetic currents. Editions Contrechamps has published a judicious selection of dense, mostly short essays, all of which have been translated into French. They include texts on musical perception and aesthetics, notes taken during a rehearsal of Mahler's 3rd Symphony, in which he emphasizes the use of affects as basic compositional material, a description of a new harmonic system based on the division of the octave into 72 tones, and an interview on his arrangement (or, to use Zender's terminology, composed interpretation) of Beethoven's Diabelli Variations.

Among the analyses of the specificities of various composers, we'll retain a short study of the mosaic-like structuring of Messiaen's works - where the apparent formal chaos forms the basis for a music of superimposed strata, whose elements/entities can grow independently of one another, in complete autonomy -, hypotheses on the effect that Scelsi's works produce on his listeners - "intuitive" music fixed once and for all in the recorded improvisation, whose transcription into a score is already an interpretation in itself, Scelsi's music is "intuitive", fixed once and for all in recorded improvisation, whose transcription into a score is already an interpretation in itself, the use of very broad temporal units and the absence of the usual parameters, an "archaic" conception of art - as well as reflections on Cage's contribution, which breaks free from the known, the stable and the conventional to open up listening without aesthetic a priori, reflecting our period of compositional freedom when no system can claim to be universal. Emphasizing that Cage did not think dialectically, but through the paradoxes of Zen, Zender asserts, as a connoisseur of Far Eastern philosophies, that only a real knowledge of the foundations of Zen allows us to understand Cage's contribution.

Karlheinz Stockhausen

After a youth particularly traumatized by the horrors of Nazism and war, the young Stockhausen, hesitating between literature and music, wrote rather traditional scores, until he discovered integral serialism, to which he was fervently converted. A willing messianist, he set out to conquer a new musical language, systematically questioning all musical parameters in search of a uniqueness inspired by his religious beliefs. The present work, also published by Contrechamps, contains the theoretical writings - commentaries, complements or justifications of his compositional approach - that punctuate this first creative period, between 1952 and 1961. The graphic representation of music, spatialization, temporal relationships, electroacoustic music, forms and structures, and the nature of sound are just some of the subjects addressed, in the context of works such as Kontra-Punkte, Gesang der Jünglinge, Gruppen, Kontakte or Zyklus that Stockhausen was developing at the same time.

Maurice Ravel: L'Intégrale. Correspondance (1895-1937), écrits et entretiens, edited by Manuel Cornejo, 1776 p., € 45.00, Editions Le Passeur, Paris 2018, ISBN 978-2-36890-577-7

Gérard Grisey: Écrits, new expanded edition with previously unpublished texts, introduced by a preface by Guy Lelong (director of publication), 388 p., € 22.00, Éditions MF, Paris 2019, ISBN 9782915794311

Hans Zender: Essais sur la musique, edited by Pierre Michel and Philippe Albèra, translated by Martin Kaltenecker and Maryse Steiber, 272 p., € 22.00, Éditions Contrechamps, Geneve 2016, ISBN 9782940068500

Karlheinz Stockhausen: Comment passe le temps. Essays on music 1952-1961, edited by Philippe Albèra, translated by Christian Meyer, 352 p., € 25.00, Éditions Contrechamps, Geneve 2017, ISBN 9782940068524