Symphony no. 5

Every Friday, Beethoven is here. To mark the 250th anniversary of Beethoven's birth, each week the Swiss Music Review takes a look at a different work from his catalog. Today, it's the Symphony No. 5 in C minor.

It's almost galling to realize that, at the same time as he was writing his Fourth Symphony, Beethoven was working on another work that would open up a completely new and different world. For the Fifth Symphony rises far above the tradition of the genre, in many respects. For one thing, in the finale, Beethoven enlarges the orchestra, and he sees fit to mention this in a letter to Count Franz von Oppersdorff (to whom the 4th symphony is dedicated): "The last piece of the symphony is with 3 trombones and a flautino [piccolo] - there are not 3 timpani, but they will make more noise than 6, and even a better noise." On the other hand, the scherzo and finale are formally linked, so that the scherzo seems to be an oversized introduction, with this transition from the dark to the radiant C major of the last movement. Beethoven repeats this astonishing effect at the start of the reprise, which even Louis Spohr, who otherwise greeted the work with restraint, hails with respect: "The last movement, with its insignificant noise, is the least satisfactory; the return of the scherzo into it, however, is such a happy idea that the composer is to be envied. It has a ravishing effect. Thirdly, Beethoven begins the first movement in a radical way: not with a slow introduction, not with a well-formulated theme, but only with a basic motif consisting of two tones and four notes, whose momentum is already arrested by an organ point in the second bar, and which is repeated in almost every bar of the movement.

With this symphony, however, Beethoven not only introduces a new musical concept, he also takes the path that leads him from Viennese Classicism to Romanticism. E. T. A. Hoffmann had already recognized this in his review of the work, published in 1810 in theAllgemeine musikalische Zeitung Leipzig: "In this way, Beethoven's instrumental music opens up the realm of the immense and immeasurable. Rays of light cross this realm in the depths of night, and we become aware of the gigantic shadows that rise and fall, enclosing us ever more tightly and destroying everything in us except the pain of infinite desire [...]. Mozart awakens the superman, the marvel that inhabits the inner spirit. Beethoven's music shifts the levers of thrill, fear, horror and pain, and awakens that infinite longing that is the very essence of Romanticism. Beethoven is a purely Romantic (and therefore truly musical) composer.

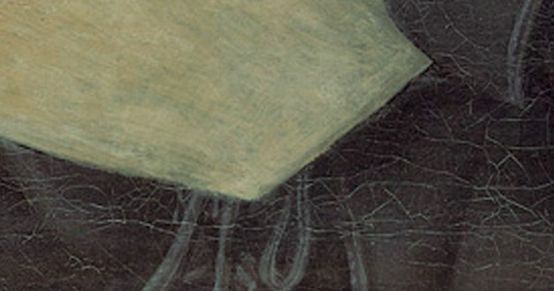

The autograph, with its many deletions and revisions, shows that the sublime described above was the fruit of Beethoven's hard work. Leonard Bernstein demonstrated this impressively in a legendary television broadcast in 1954. Link to the video. When we look back at Beethoven's worktable, we experience those four notes, heard so many times, in a totally different way.

The autograph of the 5th Symphony is in the possession of the Staatsbibliothek Berlin and can be consulted online (the various deletions at the end of the first movement can be found on pages 82-86). Link to autograph

Aufnahme auf idagio

Keeping in touch

A weekly newsletter reveals the latest column on line. You can subscribe by entering your e-mail address below, or by subscribing to our RSS feed.